Puerto Rico: The origin, evolution and future of reggaeton

Persecuted by the police and popularized on the streets of the Caribbean island, a subculture emerged in the mid-1990s that is now sweeping the world. EL PAÍS visited the home turf of reggaeton, to meet the movement’s old and new heroes

“Black Label with coconut water,” is what La Sista asks for, at a seaside bar in San Juan, Puerto Rico. She seems distant, or bored about having to give an interview about reggaeton: how it all started, what was the key to it, how it evolved. All that jazz.

“How do I explain this to you… The reggaeton of the [past] is different from the reggaeton of today, because maybe it’s less melodic. It used to be more rap-heavy. Now, reggaeton is more commercial, it’s nicer,” she opines.

Once she starts talking, she seems withdrawn rather than distant — it’s hard for her to get comfortable. Maidel Amador Canales (her real name) is a singer who’s highly-regarded by all connoisseurs of reggaeton. Yet, the 40-year-old has had an irregular career, going back to when her first manager was jailed.

Majestad Negroide (2006) is the only album she’s ever put out. She’s trying to make a comeback, with singles such as Freshy: a fusion of drill (a sub-subgenre of rap), Afrobeat and classic reggaeton, which shows her commitment to reconnect the old days of the genre with the current ones. The music video for the single was recorded in her hometown, Loíza, one of the cradles of Black culture in Puerto Rico. In it, she appears as a queen of the streets that she’s reclaiming.

“I want to give [a jolt] to those who know me from when I had my best moment and also to the new generation, who don’t know about me. [I want them to] have the opportunity to know a little about who La Sista is,” she explains, while sipping her cocktail.

She has purple dreadlocks and wears a pendant, from which a silver cross hangs. On Sundays, Maidel accompanies her mother to church, where, as a child, an elderly woman told her: “Your vocal cords have been anointed to be your instrument in life.”

La Sista’s moment came during what DJ and producer Adam Avilés calls the “golden age” of reggaeton, which he places between 2002 and 2010. Avilés made his mark working with the famous Tego Calderón on El Abayarde (2003) — an album that, two decades later, has become a classic, with songs such as the indispensable Pa’ que retocen, or that hymn of Afro-Puerto Rican vindication that is called Loíza (after the town) where he raps the lyrics: “Si una buena madre a su hijo no daña / cabrones, lambones, pal carajo España” [”A good mother doesn’t harm her son. Bastards, ass kissers, fuck Spain”].

After Tego came Don Omar, Héctor & Tito, Ivy Queen, Wisin & Yandel, Arcángel, De la Ghetto, Jowell & Randy and countless others. In 2004, Daddy Yankee put out the album Barrio Fino, whose song Gasolina became a founding hit of reggaeton, making him a star. It was the first song from this genre to be included in the Library of Congress, along with other jewels such as Like a Virgin by Madonna, All I Want for Christmas by Mariah Carey, and the tune from Super Mario Bros.

Yankee has announced that he will give the last four concerts of his career in four nights in San Juan later this year. It will mark a before and after in the history of reggaeton: the goodbye of an artist so popular that he is already historiographical material.

At the Ana G. Méndez University, researcher Tamara Miranda has written an essay entitled Del Barrio al reggaetón y del reggaetón al Grammy: las representaciones del barrio en las canciones de Daddy Yankee [From the hood to reggaeton and from reggaeton to the Grammys: the representations of the hood in the songs of Daddy Yankee]. In a telephone conversation with EL PAÍS, she explains her sociological interest in the genre. She also says that she’s desperate to get a ticket for one of the shows in which the mythical start of Gasolina, the founding slogan of reggaeton that reverberates across the world, will be heard live for the last time:

“Zúmbale mambo pa’ que mi gata prenda lo’ motore’

Zúmbale mambo pa’ que mi gata prenda lo’ motore’

Zúmbale mambo pa’ que mi gata prenda lo’ motore’

Que se preparen que lo que viene es pa’ que le den (duro!)”

“Get it?” says DJ Adam. “There were so many artists with so many songs. Everything they put out became a hit, everything! And still, to this day, you play many of those songs and today’s young people recognize them.” He puts on Guatauba (2002) by Plan B. “Like this song that I’ve played for you; as soon as it comes on, the people go crazy.” “Lo que yo quiero es una gata / para darle guata uba / uba uba guata”: the song more or less continues like this, with the singers explicitly describing what they’d like to do with their lady.

We are at Paraíso Night Club, which belongs to a friend of the DJ. We do the interview here before it opens to the public. Adam is a 53-year-old Puerto Rican, tall and calm, with the swagger of an old-school hip-hop dude. What came after that “golden age” isn’t for him. “Starting in 2010 or 2012, the voices became softer; they started using autotune or Melodyne to improve them.” He sees a monotonous panorama, lacking the originality that, he says, was demanded of each artist in the early days.

Eduardo Cabra, 44, is the founder of the iconic group Calle 13. He’s a musician and producer who has continued his career on his own, racking up awards. “The theme is the same, the sound is the same,” he laments, while having some scrambled eggs for breakfast in a cafe in his San Juan neighborhood. He believes that the music industry has appropriated the sounds of reggaeton and has been exploiting the genre on a large scale, generating an impoverished musical “monoculture.”

“In Latin music, it seems as if there’s only one path to success, and that’s wrong. In Anglo music, for example, there’s more diversity: you see Black music that’s breaking [the norms], Taylor Swift is changing things up, there’s rock, country… There are different genres that are having success. In the Latin field, nope. Right now, there’s the urban genre (synonymous with reggaeton)... and, well, Mexican regional music is doing quite well, which is cool.”

Cabra — who, with Calle 13, produced the hit Atrévete (2005), an alternative reggaeton song — calls for those at the top of the genre to start experimenting, so as to break with the current sound loop. “My head is blown away that, when someone reaches a status within music that gives them the freedom to do whatever they want, the opposite happens: they do well and then, they continue doing the same old thing, instead of doing, I don’t know, a collaboration with Björk, or with the monks from I don’t know what the hell — something that [will] break your head on a conceptual level.”

He names Rosalía as a reference of audacity. And he hopes that, with time, his compatriot Bad Bunny will take a bigger leap: “He has the resources to make a really badass record that doesn’t connect only on the entertainment side, but also on the artistic side.”

Adam Avilés, likewise, highlights Bad Bunny: “He may not have the best voice, as many say, but he doesn’t sound the same as anyone. That boy has something. He’s like the Pied Piper of Hamelin: all kinds of people follow him, of all ages. He’s attracted a different type of audience that didn’t listen to any reggaeton before. I haven’t seen that for a long time; something similar happened with Tego [Calderón].”

Bad Bunny actually sings about his diverse audience in La Jumpa — a 2022 song in collaboration with Arcángel, one of the most spectacular voices in reggaeton: “A mí me escuchan las abuelas / y sus nietecitos maleantes / tiradores y estudiantes / doctores y gánsteres” [”Grandmothers listen to my music, as well as their little thug grandchildren, shooters and students, doctors and gangsters”]. This 29-year-old artist has brought reggaeton to the top of music and global culture. It has been a long journey for a subculture that, at the beginning of the 1990s, was barely known and was actually persecuted by the Vice Control Squad of the Puerto Rico Police.

“We called it ‘underground.’ It still wasn’t known on the radio, on television, in stores,” Avilés recalls. “It was us DJs who started selling it on the street. We’d stand somewhere, open a box, and say, ‘Look, I’ve got this cassette for ten bucks.’ ‘Give me one, give me another,’ and that’s how it all started.” The genre started off as a mix of dancehall rap and reggae beats. The DJs — the true founders of the movement — would then record and add to the beat any kid who dared to rap.

Among those DJs and producers, there were key names such as DJ Negro and DJ Nelson. The one who became the most renowned, however, was DJ Playero. His legend goes back to the living room of his apartment in the working-class Villa Kennedy neighborhood, where he made his mixtapes and got Daddy Yankee — a boy who wanted to be a baseball player — started. In one of his recordings, around 1991 or 1992, Yankee shouted the word “reggaeton!”

–“Why did he say it? What was he referring to?”

–“Nobody knows, neither him nor me. It was part of a song we were putting together — a pure coincidence,” shrugs DJ Playero, or Pedro Torruellas, 58. He’s sitting in his hotel, wearing a Death Row t-shirt.

One day, in front of his house, there was a shooting. Playero went down to the street — he found Yankee on the ground. An AK-47 bullet had burst his femur. The DJ put him in the car, took him to the hospital. Baseball was over for him; Yankee only had his music left. “I thank God for that bullet,” he said in a 2006 MTV documentary.

An Uber driver named Miguel says that, in his opinion, the most successful reggaeton artists are, in this order, Bad Bunny, Ozuna and Anuel. Anuel is his favorite because his music is “for the streets.” But he makes it clear that “the king, the cangri, is called Daddy Yankee.”

Cangri comes from cangrimán: “a person of great power and political influence.” And this comes from the word “congressman” — a member of the U.S. Congress, the legislative branch of the country that has occupied Puerto Rico since 1898 (after four centuries of Spanish colonization) and maintains jurisdiction over most of its affairs. Puerto Rico is an unincorporated territory of the United States with limited autonomy. Caribbean theorist and author Jorge Duany defines it with this oxymoron: “A postcolonial colony.” This paradox is at the heart of reggaeton.

The genre has its roots in Jamaican reggae. It was distilled in a Latin country, Puerto Rico, after a previous stopover in Panama, where reggae first began to be sung in Spanish. The Dictionary of Americanisms included reggaeton back in 2010. The Dictionary of the Spanish Language admitted the term in 2014 — a bit late, if we take into account that the world had been perreando (or twerking) for at least a decade.

Perreo still isn’t included in the Royal Spanish Academy’s official dictionary. However, it does appear in the Dictionary of Americanisms: “A dancing man and a woman, bringing their bodies together and shaking their hips at the same time” — a definition that doesn’t contemplate the possibility (visible in the photos included in this feature) that two women or two men may engage in the practice. The modesty of the definition is quite ironic, especially when considering the graphic lyrics of reggaeton.

In La receta (2023) — the latest song released by Tego Calderón — we hear him say: “Los pollitos dicen pío pío y yo me río / esto se baila como si te fuera a hacer un hijo” [”The little chick cheeps, and I laugh. This is meant to be danced as if I were to give you a son”]. Not long ago, in an article for EL PAÍS, writer Martín Caparrós — with clinical sobriety — defined perreo as “a kind of dance that is free of pretense.”

According to sources at the Royal Spanish academy, perreo will be in the next edition of the dictionary, to be released later this year.

But let’s go back to Miguel, at the wheel of his Uber, crossing San Juan. He emphasizes that Daddy Yankee was “the one who started this, the one who opened the doors.” He says that the key to his success has been “his consistency.” “Yankee came and knocked out 30 songs, Wisin & Yandel came and knocked out 50 songs... Generations of [new] reggaeton singers continue to churn out commercial songs that people like, but the perreo will never be forgotten.”

One night, at the clubs in San Juan, a girl who is partying, Yashire Laureano, says that perreo has softened over the years: “People don’t dance like before, [when it was like having] sex with clothes on. So, it’s no longer so coarse.” Laureano is at the Fifty Eight club. There are Möet Chandon vibes, expensive clothes. She has dressed up with care, wearing Kardashian-style makeup.

From the smallest jurisdiction in the Spanish-speaking world (this Caribbean archipelago is only about 100 miles long from east to west) generations of reggaeton players continue to churn out hits.

RaiNao, 30, lives on her own, but she meets us at her parents’ house. She’s eating pistachios on the sofa when she says: “The urban genre has evolved immensely. I think there’s a very strong and beautiful presence of female voices.”

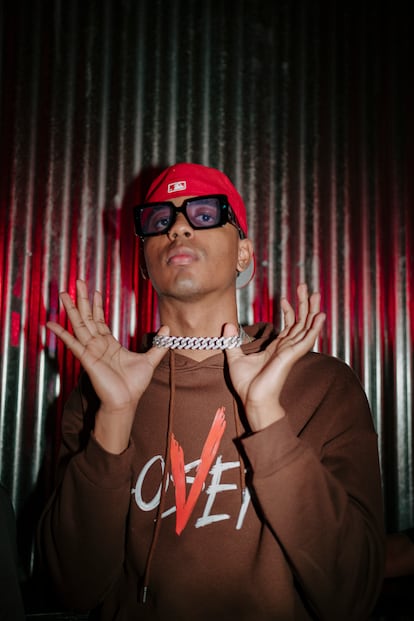

Brilliant talents like her and 27-year-old Paopao — who plays a contrast of reggaeton and melancholic tunes — are generating a lot of noise. Young Miko, 24 — who’s on her first international tour this summer — was recently included in a list of 25 musicians of the future by Rolling Stone. The magazine’s guest advisor was Bad Bunny. In addition to Miko, there are two other Puerto Ricans on the list: 26-year-old Omar Courtz and 28-year-old Villano Antillano. Courtz moves between reggaeton, trap and R&B. Antillano, meanwhile, is more of a rapper, definitely a performer.

The new generations are merging — something that always occurs in the Caribbean. The virus of reggaeton keeps mutating, but it mutates while clinging to its roots. One night, during a rehearsal session, executive producer Siggy Vázquez, 32, predicts that “the essence of reggaeton isn’t going to be lost. The [singers] combine it with other things, but the base sound of that rumbling bass will last. That, for me, is reggaeton.”

In the studio, the kids sing in the lazy trap tone, work on their badass poses, exhale thick pot smoke. The producer quickly answers the question about whether trap is considered reggaeton: “The main culture is reggaeton and it will always be reggaeton. Trap is a subgenre of rap that the boys brought from the United States — it did well in Spanish, and so now it’s developing within reggaeton.”

One of Siggy’s business ventures is the production company Full Harmony. This firm mixed LALA, by 29-year-old Myke Towers — a song that took TikTok by storm this summer and has gone on to be number one on Spotify.

During the interview with Siggy, Mambrú, 51, is in attendance. The pioneering producer rejects the label “urban music.” According to him, the industry wants to absorb “a unique, exclusive genre” — that of reggaeton.

“Hi! I’m just waking up, lol,” texts Ana Macho before responding via a voice message: the 25-year-old singer — unlike Mambrú — understands “urban” to be an umbrella term, without a negative connotation.

In different conversations with EL PAÍS, Macho defines themself (at first) as a reggaeton singer: “Because I create reggaeton, I write reggaeton, I produce reggaeton, I dance reggaeton. Reggaeton is my favorite genre of music and probably the one I’ve studied the most.” But then, the defenition changes to a “reggeaton artist from the 2000s, but non-binary and queer.” Lastly, Macho refers to themself as a “maricona” — reclaiming the Spanish slur for a gay person — “who really likes pop music and reggaeton and does both at the same time.”

The interview takes place in Old San Juan. In a little square, Macho arrives wearing black sunglasses, a black patent beret, a tight-fitting, high-necked long-sleeved shirt and military-style boots. The artist looks like a mix of a member of the Black Panthers and Victoria Adams in her earliest version of Posh Spice. In the plaza, there’s a bust of some hero.

–“Who is it?”

–“I don’t know, I’m not interested,” Macho answers nonchalantly, then jokes: “On the record: in my opinion, all the statues in Puerto Rico have been cancelled.”

The hero isn’t a nobody, although he isn’t the best-known of Latin America’s heroic men, either. Portrayed in stone is Francisco de Miranda (1750-1816), the precursor of the liberation movements across South and Central America.

Ana Macho goes on to say that, in the urban genre, “everything is moving.” There’s a lot more diversity, even though there’s still work to be done. “It’s cool that there are one or two well-known queer artists in Puerto Rico, but there are still a lot of other artists who are ignored. There are still many spaces that we need to create for ourselves,” affirms the singer and writer of Cuerpa.

Macho is somewhat satisfied with the success they have attained. “I’m doing my thing. I do it full time and, even so, it doesn’t compare to all the opportunities that a cisgender heterosexual rapper has.” They note that there’s still hatred. Not long ago, they were taking their trash out — “while wearing my yoga outfit” — and someone yelled out to them and called them a “pato” — another slur used in Puerto Rico for gay people. “I didn’t say shit to him,” they recall. “Your emotional, social, and spiritual intelligence is so beneath mine that I’m not going to bother; I’m going to keep walking and you have to deal with the karma you just earned, bro.”

Rapper Young Miko sings in Lisa: “hablando claro, tengo un problema / es que rápido me enchulo de las nenas” [”speaking clearly, I have a problem. It’s that I quickly fall for girls”]. Villano Antillano exalts herself in Reina de la Selva as a “transformista, antinaturalista / modelo bella como Evangelista” [“transvestite, anti-naturalist, beautiful model like Evangelista”]. In Tentretiene, a song about two girls in love, RaiNao sings: “me dice vamos p’al baño a arreglarnos / pero yo sé que es pa alborotarnos” [”she tells me let’s go to the bathroom to get ready, but I know she wants to mess around”].

At her parents’ house, RaiNao explains: “I write what I live — I’ve been with girls, just as I’ve been with guys. I say what I want to say, how I want to say it. That also motivates other girls and other guys to speak their truth.”

The feminine leap and diversity of reggaeton should be appreciated, especially when taking into account that the genre comes from a mysogonist narrative, which is still well-established. In the song Son Bow (1991), by the Panamanian El General, a defining rhythmic pattern can be heard, as can a homophobic rant.

In his apartment in San Juan, fashion designer Fernando Sosa, 58, recounts an episode related to this song: “I remember that I went to a gay party where they had it on. I went to the DJ and said: ‘What the hell are you doing playing such homophobic music in an environment like this?’ He replied: ‘It’s popular…’”

Today, El General is an evangelical pastor. Just like one of the greatest historical figures of reggaeton, Héctor Delgado, formerly known as Héctor El Father.

“God bless you a lot, how are things, God bless you a lot, welcome to Puerto Rico,” the former artist smiles. During his career in the music business, he rubbed shoulders with the likes of Jay-Z. Now, early in the morning at his church, he quotes Bible verses. He paraphrases Paul (Philippians, 3): “What I used to have as gain, now I consider as rubbish.”

He triumphed first as part of the duo Héctor & Tito (“baila morena, baila morena / perreo pa los nenes, perreo pa las nenas”), then solo as El Father, embracing pure gangsta reggaeton. In 2006 he sang: “Hay un rumor de guerra y de funeral / comentan que a mí se me acerca el final” [”There’s a rumor of war and of a funeral; they say that the end is near for me”].

But, despite all of this success, he fell into a depression. He says that he put a gun to his temple several times and that he nearly jumped from the 19th floor of a hotel in New York City. He tells EL PAÍS that he was earning between $2 and $3 million each year from his music, but that his life had no meaning. In 2008, he left the industry and joined an evangelical church. Some say that he did this not so much because he wanted to save his soul, but because he was worried for his life. He denies this, although he admits that he had many enemies during his time as a gangsta rapper. Delgado claims that his decision was existential: he says he had a revelation.

Over and over again, he glorifies the name of the Lord, rejecting his past as Héctor El Father and lamenting his harsh reggaeton: “When I see everything I caused, I’m not proud, because I confused many young people. I have friends who serve the Lord today; before, they were drug traffickers. They tell me that they went ‘hunting’ [while listening to] my songs. When we talk about hunting, we mean killing other people.”

Delgado, however, shows some satisfaction when remembering that Baila Morena (2004) was the first reggaeton hit in Europe. Both DJ Adam and DJ Playero mention a song by El Father as an exceptional piece in the history of reggaeton: Tú quieres duro. In the song, a woman sings “dale duro papi más duro” [”daddy, give it to me harder”]. The woman who gives voice to that line is Glorimar Montalvo, or Glory. Now 44, she’s a figure of great interest, because she did the choruses for many songs that went on to become hits, including Dale don Dale, by Don Omar, or Gasolina, by Daddy Yankee. Montalvo did not respond to interview requests from EL PAÍS.

In his essay Reggaeton: A Latin Revolution [Reggaeton: A Latin Revolution], Pablito Wilson interprets the faint trace that remains of Glory’s contributions to the genre as a sign of those times: “It would be good to ask ourselves if the world was ready for Gasolina [to have been] a duet song and not the solo release that it finally was; the first woman to have a glimpse of global fame [in this genre] came as a man’s invisible companion.”

A female singer who overcame all the barriers in the early days of reggaeton was Ivy Queen, 51. She stood out from the beginning, made a name for herself and became the star that she is today. Her latest song, Quiero Bailar — produced by DJ Adam — is seen as a feminist anthem and chanted during marches on International Women’s Day.

La Sista corroborates how exclusive the environment was at the beginning of the 2000s. “For me, it was quite difficult, because when I started, there weren’t many women singing. This genre has always had more boys than girls.”

As for the street violence that fueled the songs of El Father, it continues to be a central problem in Puerto Rico, which, for decades, has been a gateway for drug trafficking into the United States. According to the latest official data (2019), the firearm homicide rate exceeded twice the world average (making up 91% of total homicides compared to 42.7%). Social marginalization is a continuing issue, with 40% of families living below the poverty line, while gangs and shootings are constant. The “hood” connection with urban music continues to be relevant.

Last June, the reggaeton singer Pacho el Antifeka was shot to death at the age of 42. In 2021, the same thing happened with the 32-year-old singer Jehza. As with Yeruza, 22, in 2020, or Kevin Fret, 25, in 2019. Fret claimed to be the first openly gay Latino trap artist. A few weeks ago, 23-year-old Luar La L — a rising figure in trap, whose role model, Anuel, spent 10 months in prison for illegal possession of weapons — was arrested with another person. They had guns and dozens of bullets on them.

The contemporary world of reggaeton in Puerto Rico — its rhythms, contents and attitudes — continues to have similarities with its beginnings. Although, at the same time, it has diversified quite a lot. There’s no doubt that the journey has been amazing, one of historic dimensions: from the obscurity of the 1990s, to the illustrious Bad Bunny wearing a white suit by Jacquemus at the ultra-elitist Met Gala. This jump from being held in contempt by so-called “high culture” to sudden adulation already happened in the 1970s with salsa.

Historian Jorge Duany explains that the two genres had a negative reception “because of their popular, hybrid, Afro-Antillean character, as well as their close ties with youth from the lower classes.” Salsa and reggaeton, he notes, “overcame obstacles, until they became the main musical exports of Puerto Rico and other countries, as well as indisputable symbols of the cultural identity of Puerto Ricans on the island and in the diaspora.”

Sociologist Petra Rivera-Rideau — author of the essay Remixing Reggaetón (2015) — maintains that, from the beginning, the “prejudice” against the genre was a “symptom of racism and classism in Puerto Rico.” “This doesn’t mean that reggaeton doesn’t have problems,” she clarifies, “but rather that prejudices against the communities that created reggaeton influenced how it was perceived. This includes academics. [According to them,] reggaeton wasn’t a culture that had value to be studied.” Rivera-Rideau sees academic interest in the genre growing, but notes: “There’s still a lot of prejudice against reggaeton being studied in universities.”

Intertwined with the appreciation for reggaeton — a progressive process that has lasted two decades and continues — there has also been an affirmation of the linguistic singularity of Puerto Rico. Maia Sherwood — a member of the Puerto Rican Academy of Language and an attentive observer of the reggaeton phenomenon — says that the genre is “close to the youthful, informal, spontaneous, direct, creative way of speaking,” which highlights a growing pride in the Puerto Rican dialect and the loss of the “inferiority complex” of being a type of Spanish that some saw as inferior.

Today, a multitude of Spanish-speaking young people — as well as those who speak other languages — enjoy the madly hybrid lyrics of reggaeton. For those who don’t speak Spanish (or, more precisely, Puerto Rican Spanish), it would almost be counterproductive to translate songs like Riri, by Young Miko: “All my bitches bad / all my bitches yummy / la baby trabaja / she’s all about her money / sabe que está ricota / sabe que es una mami.”

Sherwood thinks that this flexibility of reggaeton’s language is influenced by a current that transcends this form of cultural expression: “It may have to do with the spirit of the times Young people are validating diversity in all its forms. They’re refusing to suppress or alter authentic features of their expression to satisfy social or commercial demands,” he says from his home in San Juan.

New generations of linguists have begun to pay more attention to the richness of reggaeton. An example is a research investigation conducted by Cristina Maymí, which is about to be published and consists of a lexicon of Puerto Rican Spanish in reggaeton lyrics. Her work attempts to remedy the lack of studies (with a lexicographical focus) of this authentic language. She has registered 128 new slang words and phrases, such as está to’ Gucci, which indicates that everything is fine and in order; flow, or a person’s style or way of behaving; and rebuleo, which refers to a rowdy discussion or disagreement.

And, at the top of the entertainment industry, Bad Bunny is the most powerful voice when it comes to reclaiming reggaeton and its roots. At the last Coachella festival in California, where he was the headliner, he screened a video about the origins of salsa and reggaeton. “It served to emphasize the importance of the work that Latino workers have done for years in the music industry,” says cultural journalist Hermes Ayala.

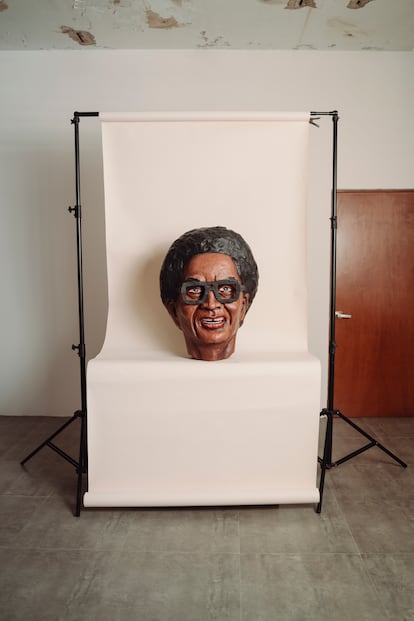

At the last Grammys, held in Los Angeles, Bad Bunny performed while surrounded by big-headed Puerto Rican historical figures, known as cabezudos, which belong to the theater group called Agua, Sol y Sereno. In the collective’s workshop in San Juan, its founder, Pedro Adorno, 55, sees that singer’s decision as having to do with “identity, with the rescue of historical memory, with the cultural efforts of many years of political movements and social and historical consciousness.”

From his neighborhood in San Juan, Adorno lived through the prehistory of reggaeton. It was the 1980s: hip-hop culture was gaining ground, via the coming and going of Puerto Ricans who had one foot on the island and the other in the United States (especially in New York). Back then, Adorno was a street breakdancer, like DJ Adam. In the late 1980s, Adorno took a different path, going to university and getting into experimental theater. With Agua, Sol y Sereno, he has developed a crossover project between avant-garde and popular culture. His collective is characterized both by its theatrical practice and its participation in local folklore. For him, getting a call from Bad Bunny served as recognition of the commitment they’ve made since the 1990s, to combine modernity with Puerto Rican tradition.

Most of the cabezudos were already made. However, the singer expressly requested two new ones: that of Felisa Rincón de Gautier — the first woman mayor of a capital in America — and that of his revered Tego Calderón. Everyone talks so much about him, yet he’s extremely difficult to reach. Calderón did not wish to be interviewed for this feature.

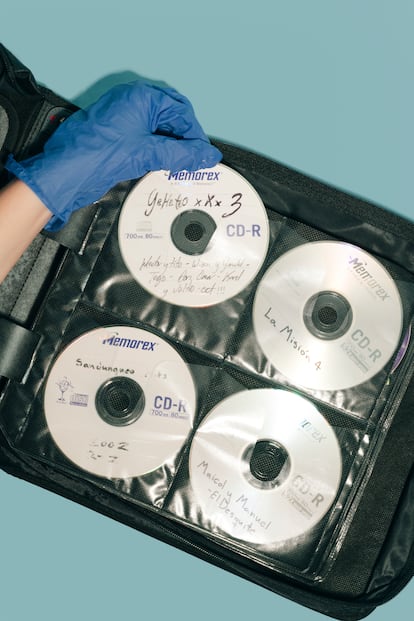

If Bad Bunny is the voice among the elite, at a more down-to-earth level, there are initiatives such as the Hasta ‘Bajo Project, which seeks to safeguard the history of reggaeton, while sharing it and educating the public about the phenomenon’s past and present. Gabriela Sepúlveda, a member of the project, explains that they try to fill the “gap” in the conception of reggaeton as heritage. “The Institute of Puerto Rican Culture, at the moment, doesn’t include reggaeton in its collection and documentation plan, although they’re aware of our work and they value it.”

Right now, they’re a modest collective, made up of seven volunteers, with a considerable digital archive. This was donated by Juan Arroyo, who created the first website about the genre in the 1990s. Other materials are kept in a small warehouse in San Juan. One of the jewels of the collection is a yellow g-string, or gistro amarillo — a thong that was distributed as an advertisement for the famous song of the same name by Wisin & Yandel.

To take out the article of clothing for it to be photographed by this newspaper, Sepúlveda puts on a pair of latex gloves. She handles the fabric as if it were a Vermeer — a treasure of its generation.

The dream of the Hasta ‘Bajo collective is that, in the future, there will be a Reggaeton Museum, where future generations can understand the contemporary history of their country by contemplating a yellow g-string. Because the g-string isn’t really a g-string. It’s Puerto Rico’s heritage.

EL PAÍS asked the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture if it had carried out — or had plans to carry out — any study or activity related to reggaeton. The island’s main governmental cultural body acknowledged receipt of the query, but did not answer.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition